13 Aug The Story of Indian Cotton

The Story of Indian Cotton: As we enter the sixth month of the pandemic I sit in disbelief, bewildered at the might of the virus- something that has incredible power but molecularly so small. This destructive virus almost feels like prescience as I consecutively write about how mankind has manipulated the existence of indigenous cottonseed, another ‘small’ yet ‘mighty’ being of nature.

The Discovery of Indian Cotton

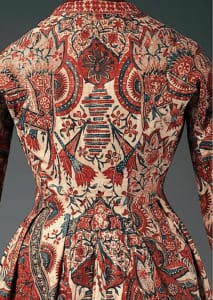

Marco Polo was a Venetian merchant, explorer, and writer who visited India in the 13th century. He marveled at the sight of the six-yard Indian cotton trees that produced the softest cotton balls. These cotton balls were transformed into the finest muslins. These Indian cotton fibers were ripe with cellulosic content so they could easily absorb dyes that created stunning colors. The vibrant colors of this painted Indian cotton, originating from the coast of Coromandel, especially Masulipatman, are still visible in various museums today. This type of cotton represents the finest examples of cotton, colors, and craftsmanship from India.

When the British arrived in India, they had little knowledge of cotton as the primary materials used for their dressing was linen or wool. The British merely utilized cotton for candle wicks.

The Indian cotton plant was once considered a royal plant. Indian cotton was once as light as dewdrops and caused the whole world to take notice. Unfortunately, nowadays cotton has to compete with synthetic fabrics.

Interestingly, there is a curious myth related to Indian cotton from Europe in the middle ages known as ‘The Vegetable Lamb.’ As per the myth, the fruit or seed pod of this particular tree (which no doubt was the cotton tree) encased a little lamb when it burst fully open. The fleece of this ‘lamb’ was the purest white. The native inhabitants of these countries, where these ‘lambs’ were from, would weave this material to make their garments. (Source: A frayed History, Journey of cotton in India)

Subsistence Farming Using Indigenous Indian Cotton Seeds

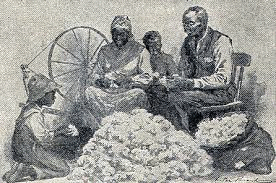

In India, cotton was initially a subsistence crop. Farmers inherited and guarded indigenous seeds that naturally adapted to the local soil and climate of their region and did not attract any out of the ordinary worms. Additionally, the making of cotton fabric was an activity that involved the whole community. Farmers would cultivate the cotton crop, every house in the village would be engaged in making a piece of cloth, spinners would spin the cotton into bobbins of cotton thread, and weavers would weave.

There was no electricity, chemicals, or greed. Instead, there was craftsmanship, nature, and camaraderie in the supply chain. The purpose of this style of farming and fabric making was to enable the survival of the whole community. Therefore, various crops of different natures were cultivated together so there was always at least one successful crop as a source of livelihood for the whole community. The practice of cultivating multiple crops together is known as polyculture. It is a boon for nourishing and enhancing the micronutrient value of the soil.

Sadly, this prosperous system was disrupted.

The Arrival of the Colonizers: Subsistence Crop to Cash Crop

When European trading companies started sailing directly to India from 1498. They were carrying enormous quantities of Indian cotton back to Europe. These brightly colored cottons from India impacted how Europeans dressed themselves and furnished their houses. The quality was such that the fabric hardly got stains as well as it had resistance for washing treatments. As a matter of fact, the demand grew to a point that there was a threat to the local textile industry of France and Britain. These European nations imposed bans on the use of these cotton whether for clothing or furnishing.

When European trading companies started sailing directly to India from 1498. They were carrying enormous quantities of Indian cotton back to Europe. These brightly colored cottons from India impacted how Europeans dressed themselves and furnished their houses. The quality was such that the fabric hardly got stains as well as it had resistance for washing treatments. As a matter of fact, the demand grew to a point that there was a threat to the local textile industry of France and Britain. These European nations imposed bans on the use of these cotton whether for clothing or furnishing.

Read More The story of Printed and Painted Cottons from India

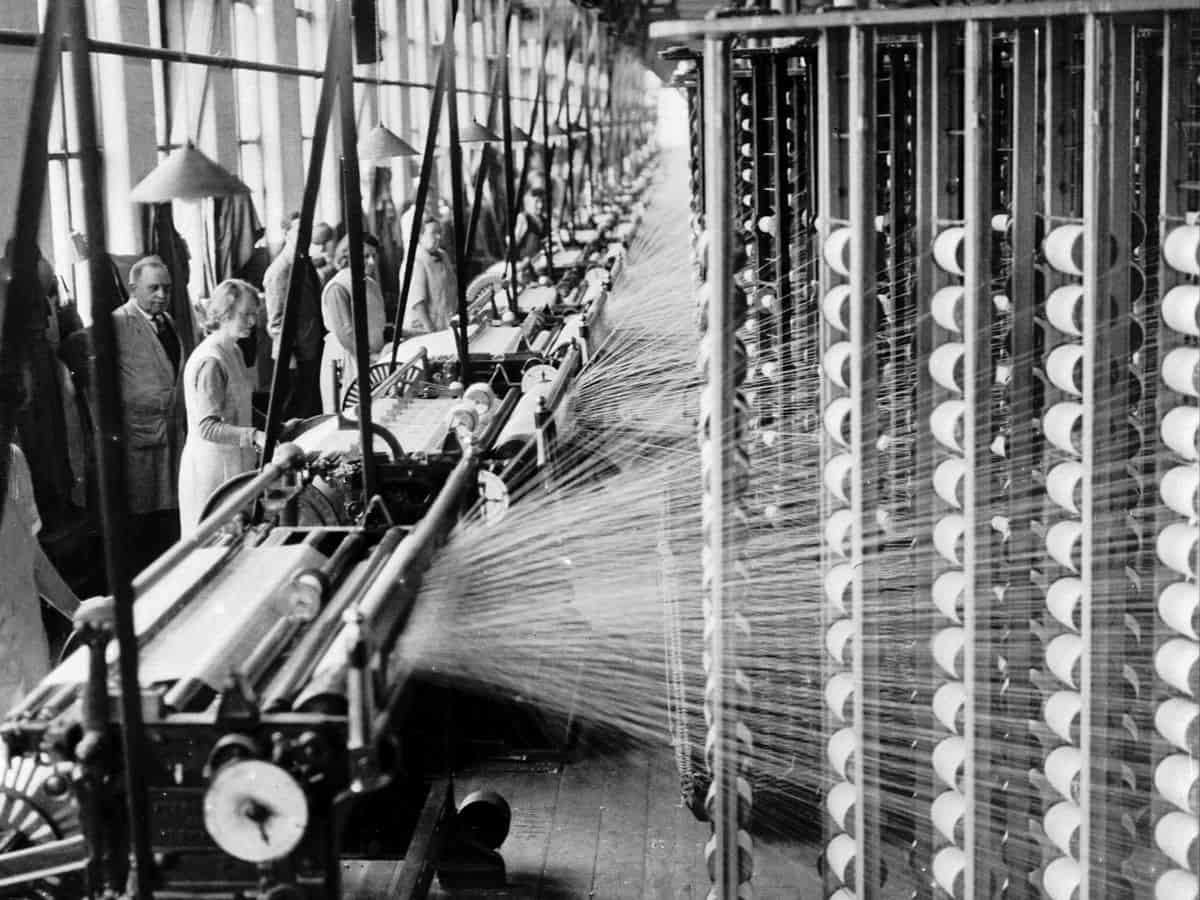

The British did not appreciate the local weavers and spinners in India. They wanted the local craftsmen to adapt to modern technologies to expedite cotton production. Faster cotton production meant more money for them. First, they introduced the spinning mills. With this new setup, the farmers sold the cotton to the spinning mills, located far away from the farms. The spinning mills spun bobbins of threads in standard quality and sold them to the weavers. This new process increased the distance between the farmer and weaver and left the farmers and weavers at the plight of the spinning mills. Time-honored practices were disrupted.

After the introduction of the spinning mills, during the industrial revolution, weaving mills in Lancashire started weaving cotton from India. The British exported bobbins of Indian cotton thread from the spinning mills to the weaving mills in the UK. The finished product would then return to India to be sold as finished, mill made, bulk cotton fabrics. These fabrics were the first product exported from the West to the East. This new system reduced Indian weavers and spinners to complete penury, and in some cases total obsolescence.

The Migration Away from Indian Indigenous Cotton

Since industrial machinery was now being utilized in India (and for Indian grown cotton), there was a need to cultivate cotton that was better suited for this application. This marked the beginning of the end of cotton farming using indigenous seeds. Indigenous seeds produced short-staple fibers that required to be painstakingly spun by hand. This type of cotton did not work well on the machine. The British started looking for ways to cultivate machine-friendly, strong, and long cotton fibers which could be machine-spun. At first, the British introduced American cotton varieties such as ‘Fine Sea Island Cotton’ and ‘Bourbons’ systematically in India. They set up experimental farms all over the country.

The Industrial Revolution marked the beginning of the end of India’s biodiversity in short-staple cotton. As is the case in business, supply follows demand. Indian farmers now catered to mills in Manchester that wanted longer-staple cotton.

Beyond damaging the local biodiversity of cotton varieties in India, the introduction of foreign cotton varieties introduced another problem-pests. The American cotton crop attracted more than 166 varieties of pests. This led to the use of a variety of poisonous insecticides and pesticides. These toxic pest killing sprays took a toll on the health of the land and the farmers who ended up inadvertently inhaling the chemicals as they applied them.

The Evolution of Cotton Varieties in India:

From American to Hybrid to Genetically Modified varieties

In 1970, Indian scientists researched and developed the first hybrid cotton called Hybrid-4. This cotton was a mix of Indigenous and American varieties of cotton seeds. However, even with the Hybrid-4 seeds, the pest issue continued. This led to a very problematic decision in the history of Indian cotton cultivation. India agreed to use Bt Cotton (or GMO- Genetically Modified Cotton) which has been genetically infused the cottonseed with toxic chemicals to kill pests that attack the plant.

Initially, Bt Cotton had promising results. It gave an excellent yield, presented a long staple, and warded off pests on its own without the use of additional pesticides. However, with time these pests evolved. They developed immunity to the pest killing chemicals that were a part of the GMO seeds. Stronger chemical pesticides were then needed to kill the evolved pests. The destructive cycle continued. The soil, which once gave life and nutrients to the plant, became ridden with toxic chemicals. Additionally, these pesticides are broad-spectrum, killing all bugs (good and bad) thus hampering the biodiversity of the soil.

Today, 96% of the land in India is under Bt cotton cultivation. Nearly 90% of cotton farmers in India are on a downward spiral of debt and suicides because they cannot see a way out. Read more on the supply chain and the adverse effects of GMO cotton seeds in the below article.

(HOW DO YOU SOURCE SUSTAINABLE COTTON)

The Socioeconomic Effects of Cotton Worldwide:

Report from the Environmental Justice Foundation, 2007

Although the majority of cotton-fiber products are sold to consumers in wealthy nations, up to 99% of the world’s cotton farmers live and work in the developing world. Almost two-thirds live in India (10 million) or China ( 7.5 million). These farmers, unlike their counterparts in the US or Australia, are predominantly members of the rural poor. They often cultivate cotton on plots of less than one-half hectare or on a farm containing other crops as a means of supplementing their livelihoods. In total, farmers in the developing world are responsible for over 75% of global cotton production. Those in China, India, Pakistan, Uzbekistan, and Brazil account for 55% of the world harvest.

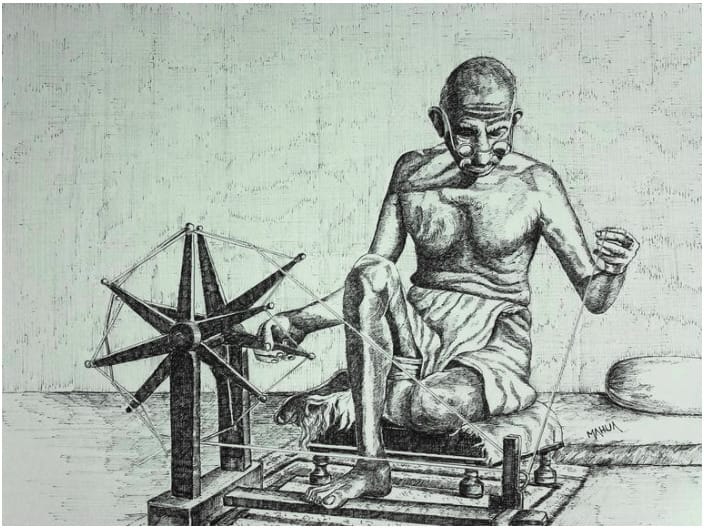

The Swadeshi Movement in India

The state of West Bengal in India was becoming a mighty power of nationalist sentiments, a threat to imperial rule. To control these sentiments, the British decided to partition Bengal and create a separate country (now Bangladesh) out of Bengal. The Indians resented this decision. They demonstrated their resistance to this partition by boycotting British goods and buying exclusively local, Indian-made products. The people resorted to burn their British clothing, refused to buy imported sugar, and protested stores that sold foreign goods. This is ‘Swadeshi’, or the economic self sufficiency movement. The revival of indigenous industry, which at such an early stage, was born out of this movement.

Read more Khadi or Khaddar- How is khadi philosophy applicable today

Although India has lost many of its indigenous seeds forever, there are still some initiatives committed to saving strains of indigenous cotton seeds. We are working with them on rebuilding the traditional Indian farming practices. These practices are inherently sustainable, organic, and regenerative. They require less water, no chemicals, and a lot of love and patience.

As we use this extremely important downtime to research the impacts of cotton cultivation on mankind and the environment, we feel it imperative to share these stories with you. Please stay connected with us in this space to read more on cotton.

Thanks

Nidhi Garg Allen

Founder & CEO

Marasim.co

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Nidhi Garg Allen is an alumnus of Parsons School of Design and Adjunct Professor at the Fashion Institute of Technology. She is a technologist turned artisan entrepreneur and the founder and CEO of Marasim. Marasim based in NYC is committed to preserving artisanal textiles that make use of regional techniques without uprooting craftspeople from their native communities

Nidhi Garg Allen is an alumnus of Parsons School of Design and Adjunct Professor at the Fashion Institute of Technology. She is a technologist turned artisan entrepreneur and the founder and CEO of Marasim. Marasim based in NYC is committed to preserving artisanal textiles that make use of regional techniques without uprooting craftspeople from their native communities

No Comments