02 Apr The Story of Cotton in America and How it is linked to Cotton Production India

Cotton was the primary commodity of the first days of an Industrial production system that changed the world.

With the arrival of the British East India Company in India and their overlordship on the cotton manufacturing (among other things) on the Indian Subcontinent, the ever so romantic and prosperous Story of cotton and cotton farmers that I discussed in my earlier post came to an erratic end.

SEED SELECTION AND GROUND PREPARATION FROM HISTORY OF SUSTAINABLE COTTON

READ MORE ON OUR COTTON SERIES

I will talk more about the India story at the end of this article. Let us first look at the Story of cotton in America.

Cotton has been growing forever in the South American continent and the West Indies. The natives there had a great skill of making it into clothes. Mexico, Peru, Brazil, and Africa were already making cotton clothes. However, in North America, the cotton seeds arrived in the Eighteenth Century. The best guess is that these were the varieties of cotton from the West Indies.

In the words of Meena Menon and Uzramma in their book ‘A Frayed History, the journey of cotton in India.’

“The land wrested from native Americans and cleared of its virgin forests was fertile. Slave labor was cheap, and cotton began to be produced commercially for the first time, grown and picked by enslaved men, women, and children. In 1859, as many as sixty thousand Delta slaves produced a staggering 66 million pounds of cotton.”

PLANTATION BASED COTTON MANUFACTURING IN AMERICA

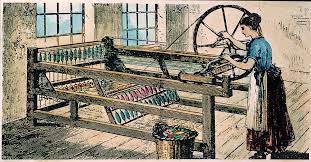

This massive plantation-based manufacturing of cotton needed new ways of ginning, carding, or weaving cotton. There was colossal slave labor at work at the plantations under inhuman conditions; still, there were needs for mechanical intervention to meet the scale of production.

The first mechanics produced was a SAW GIN invented by Eli Whitney in 1793. It has teeth that could pull the lint from the seed. Although it damaged the fiber, while snatching the lint from the seed no comparison to the careful ginning by the human hands. However, I assume that this invention must have made the life of the plantation workers easy as compared to the amount of handwork they might have to put in ginning on large cotton plantations. Nevertheless, the efficiency achieved by mechanized ginning proved to be a forbearer to the further expansion of the farms and cotton plantations.

Mass ginning needed mass packaging as this cotton needed to be transported to carding, spinning, and weaving centers. Thus came the technology of pressing the cotton into bales, starting with a screw press machine to hydraulic machines to more modern pressing machines that could press soft cotton fibers into blocks as dense as wood, thus completely changing the whole constitution of soft, humble cotton fiber.

Profiteering became the norm at these cotton plantations. This was early capitalism.

Meanwhile, in England, the Industrial Revolution was taking hold. There were aggressive research and development towards creating spinning and weaving machinery. In 1782 the steam engine was invented, and spinning and weaving machines were set up. Soon, British spinning and weaving technology consumed the humungous amount of bales of cotton produced at the cotton plantations in America.

Meanwhile, in England, the Industrial Revolution was taking hold. There were aggressive research and development towards creating spinning and weaving machinery. In 1782 the steam engine was invented, and spinning and weaving machines were set up. Soon, British spinning and weaving technology consumed the humungous amount of bales of cotton produced at the cotton plantations in America.

Who did the Empire sell this machine-made cotton to? Can you guess ?

These compressed cotton bales coming from America were suitable for the British machinery in terms of the fiber’s strength and length; therefore, this kind of cotton became a new standard, a new norm for the Empire.

It was the turn of Indian cotton farmers, ginners, spinners, and weavers to bear the brunt of this standardization and machine inclusion in cotton manufacturing. The cotton obtained from various seeds from different regions of India was all thrown together in the ginning machine to get a uniform output.

The American variety of cotton seeds was soon introduced on the Indian soil to produce the cotton suitable for the British spinning and weaving machines. A lot has changed and happened since then in the name of increasing the ‘yield,’ leading to what I said at the beginning of the article -an erratic end of a grand love affair. More on it later.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Nidhi Garg Allen is an alumnus of Parsons School of Design and Adjunct Professor at the Fashion Institute of Technology. She is a technologist turned artisan entrepreneur and the founder and CEO of Marasim. Marasim based in NYC is committed to preserving artisanal textiles that make use of regional techniques without uprooting craftspeople from their native communities

Nidhi Garg Allen is an alumnus of Parsons School of Design and Adjunct Professor at the Fashion Institute of Technology. She is a technologist turned artisan entrepreneur and the founder and CEO of Marasim. Marasim based in NYC is committed to preserving artisanal textiles that make use of regional techniques without uprooting craftspeople from their native communities

No Comments