08 Jan The Fascinating Textile Crafts of Japan

Textile Crafts of Japan : I had a pink hand-painted pajama set as a child, which came in an artful box, with the inside flap mirrored and beribboned. I loved this so much I never actually wore it but pulled it out at intervals to admire it. This was my first exposure to the miracle of Japanese crafts.

Like India, Japan has a fascinating history and reverence of craft, and very often for the same reasons. Japan was an isolated island for much of its history, and the basis of much skill was rural needs and indigenous materials. Craft evolved for the product to be used and not as an art form, but as it developed, very often, the process and product became increasingly sophisticated. Japan has the Wabi Sabi concept as the bedrock of much of its craft: briefly the beauty in imperfection, which strongly influenced its craft forms.

Craft in Japan is a broad field, but I will examine the most important textile crafts in this article.

Boro and Sashiko Textile Crafts of Japan

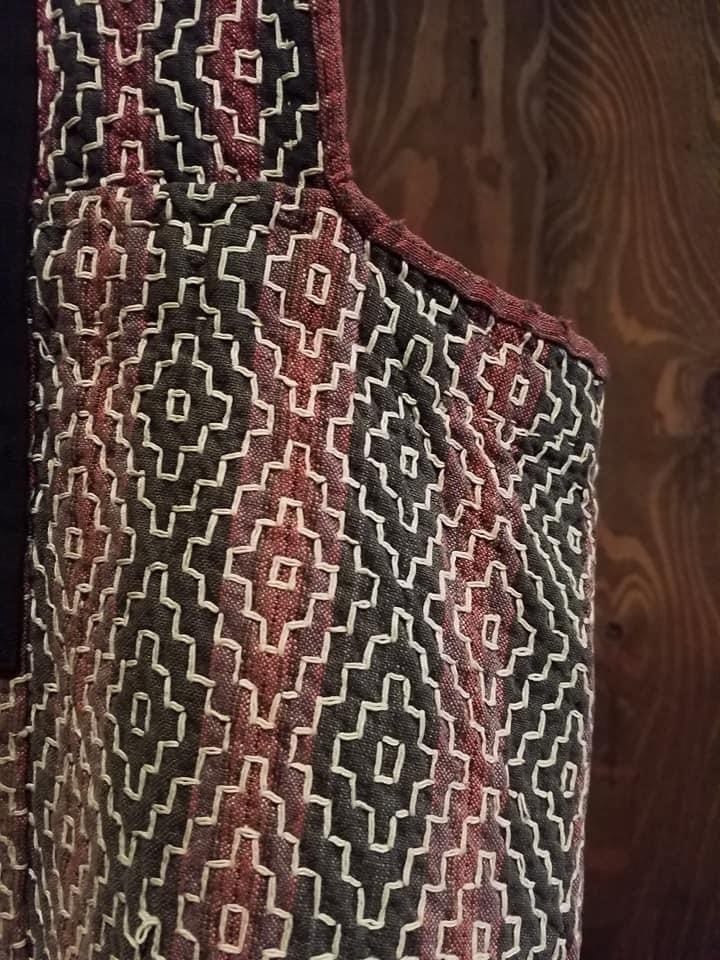

Sashiko (literally “little pierce”) going back to the 17th century is very similar to the Indian Kantha, a decorative running stitch used for reinforcing old textiles. It has traditionally been used for patching, quilting, embroidery, and stitching old clothes together as a means of upcycling. All done in Indian Kantha as well. The difference is that Sashiko is done traditionally with white thread on indigo, though now there are colored variations too.

In contrast to Japan’s gorgeous silk fabrics, sashiko is considered a “folk textile” because it was produced and used by the peasant classes. Sashiko was winter work for women from farming or fishing families, who used the technique to extend the life of worn fabrics, mend clothing, and make it warmer by stitching layers together.

Sashiko designs are based on geometric patterns, inspired by waves, mountains, bamboo, the double cypress, and other natural phenomena, flora/fauna.

Sashiko, now commonly used to repair blue jeans, has been widely adopted by Japanese designers such as Yohji Yamamoto

Boro

The word boro means tattered or repaired and is based on the Japanese word boroboro. When cotton was unknown or scarce in Japan, hemp-based textiles were continually repaired and patched, using Sashiko or running stitches. Entire garments were cut up and patched or quilted together, sometimes to the point that it was hard to tell which the original fabric was.

As Japan became prosperous after the Second World War, boro passed from popularity. It was considered embarrassing as a reminder of poverty.

In current times, boro is regarded as an art form, with old pieces selling for enormous sums of money. Brands like Kapital use the boro technique in jeans, totes, and jackets.

Both boro and sashiko as craft have influenced modern trends for distressed clothing, particularly in denim.

Katagami and Katazome Textile Crafts of Japan

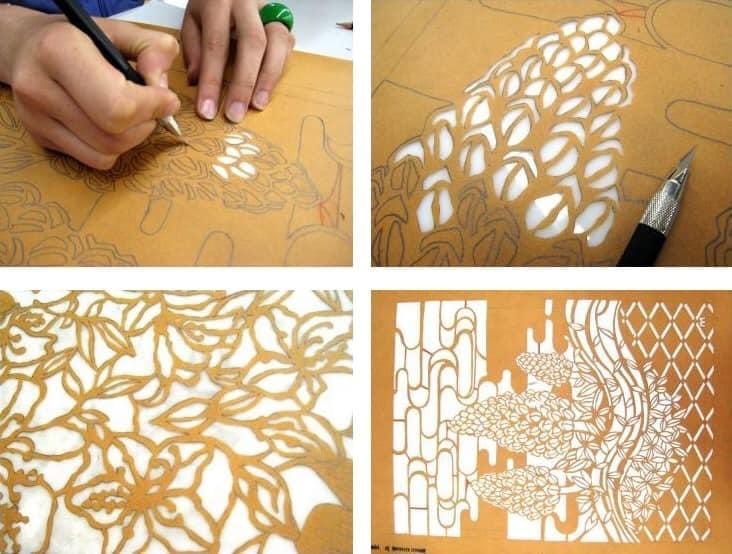

Katagami and Katazome are complementary crafts, where katagami is the art of cutting paper stencils using multiple layers of glued washi paper. The entire process is done by hand, using a sharp knife. Once the stencil is ready, it can be used repeatedly.

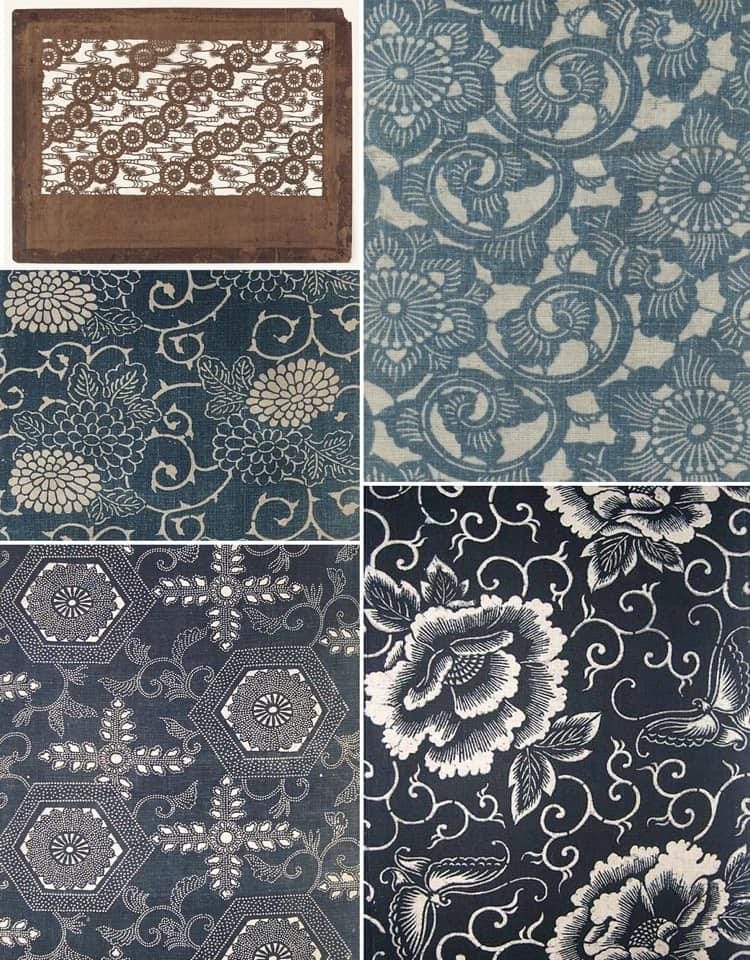

Katazome is the art of dyeing textiles using these stencils. The stencil is placed on the cloth, and a rice paste is applied as a resist with a brush. Once dry, the fabric is dyed, most often in indigo. The rice paste is then washed away, revealing the completed design.

These designs have profoundly influenced the Arts & Crafts and Art Deco movements, something I mentioned in my article on Art Deco.

A beautiful variation on katazome textiles is the Bingata Okinawa, where the patterns are far busier and more colorful, based for the most part on flora and fauna. Since these are multicolored, dyeing is repeated several times, going from light to dark.

Bingata textiles have traditionally been used only at festivals and weddings because of the complexity of the process.

Kasuri Textile Crafts of Japan

Kasuri means ‘to blur’ and the craft involves resist dyeing the yarn before weaving, completely like Ikat. A blurred appearance characterizes the finished pattern. The difference from Ikat is that Kasuri often uses only indigo, white and brown, in keeping with the Japanese aesthetic.

Kasuri, like Ikat, can be either warp or weft dyed. When both are dyed, that process is called tate Yoko gasuri, just as famous and complicated as the double Ikat of India.

I find the contemporary Japanese attitude to craft laudable. Unlike India, craft in Japan is revered. Designers have widely adopted it, both Japanese as well as international. The origin of the craft is always acknowledged, again unlike Indian craft, which very often goes unacknowledged by the user. Something Indian craft must learn from.

Read More

PAISLEY A GENUINELY GLOBAL MOTIF IN THE DESIGN WORLD

FRENCH ART DECO TEXTILE MOVEMENT’S STRONG INFLUENCE ON DESIGN

THE INDO-FRENCH ART CONNECTION

MICRO MOSAIC A POPULAR ART FROM THE 19TH CENTURY

MATISSE’S ART AND TEXTILES. HOW TEXTILE STIMULATED HIS CREATIVE POWERS TO A NEW PICTORIAL REALITY

MUGHAL & DUTCH: A CULTURAL BRIDGING OF 2 GREAT ARTISTIC TRADITIONS

BOOK VICTORIA & ALBERT PATTERN: SPITALFIELDS SILKS

INDIAN FLORAL PATTERNS IN DESIGN AND TEXTILES

AUTHOR BIO

Mira Gupta is a well-known curator and designer in craft-based luxury. She has had working stints with Fabindia, Good Earth, and Ogaan to promote the cause of craft. She is deeply interested in art, travel, architecture, and culture.

Read more articles by the Author HERE

No Comments