24 Jul Headgear, A Style Statement And Much More

Headgear in contemporary times is associated with the outdoors, with events like Ascot, or with pop culture. There are notable exceptions, like the clergy or royalty. And of course, other than where headgear is associated with religious affiliations, it is no longer de rigueur as a part of daily life. This wasn’t always the case. There was a time when headgear was an essential part of apparel, denoting status, religion, and profession, right up to the early 20th century.

Early History of Headgear

Plenty of evidence is available, even from ancient history, of headgear worn by the elite in the military, religious or royal contexts. Terra cotta figurines dating from 2300 BCE from the Indus Valley civilization wear headgear. The figures in the cave paintings of Les Trois, France, though their hats look like antlers. Caves in Algeria have men wearing headgear that looks remarkably like turbans.

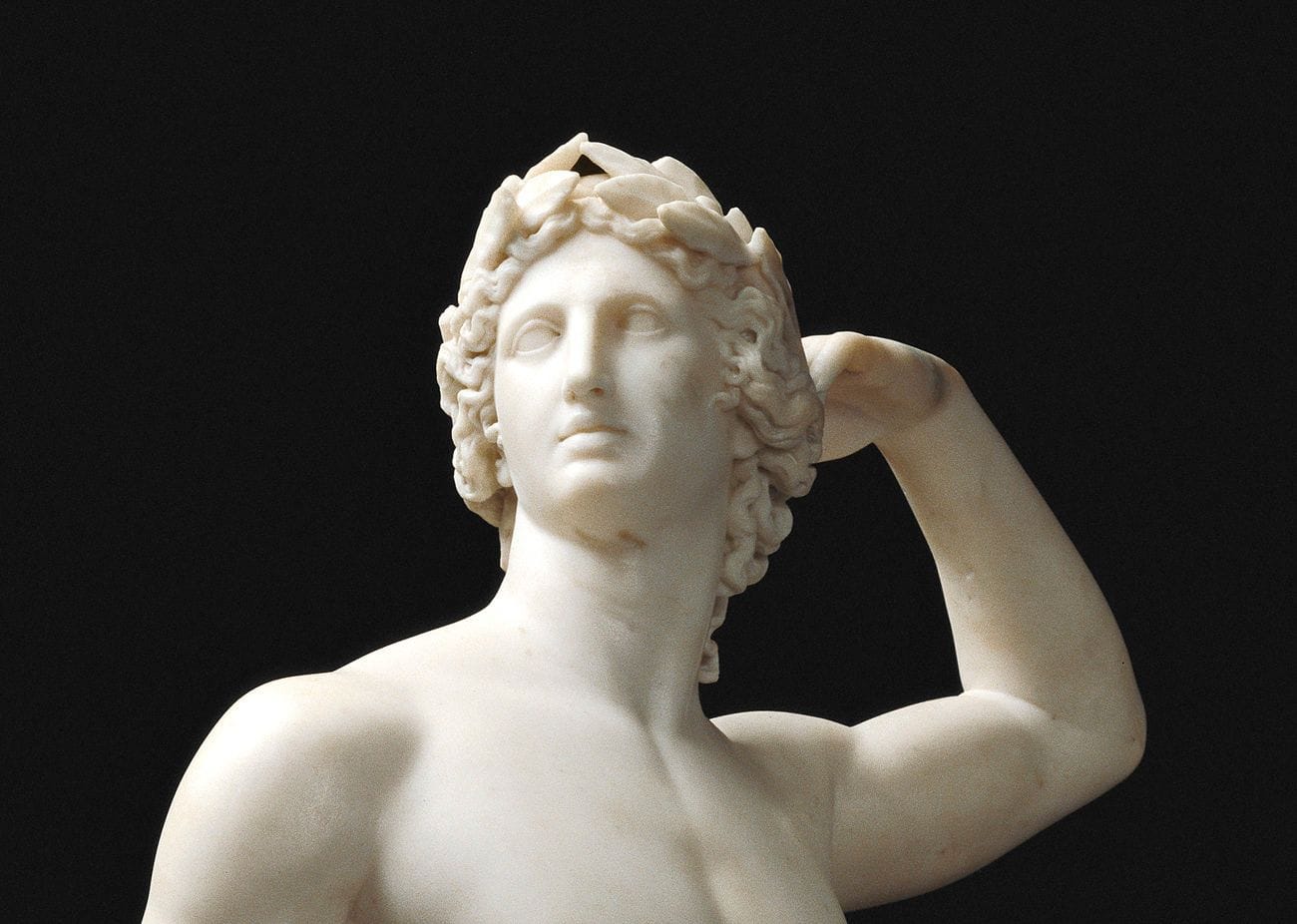

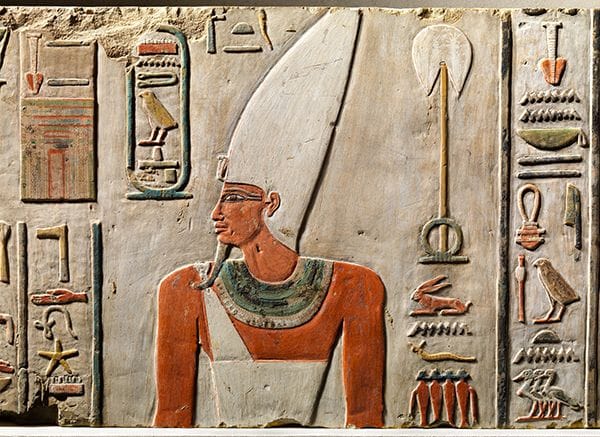

Moving down in the continuum of history, wall paintings in Egypt show crowns for royalty and a pleated linen square for commoners. Similarly, there is ample evidence from Greece and Rome of headdresses like wreaths. Made of ivy or Myrtle, these were given as a marker of prestige.

The later history

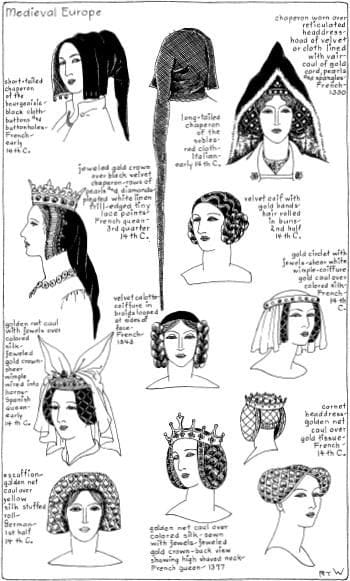

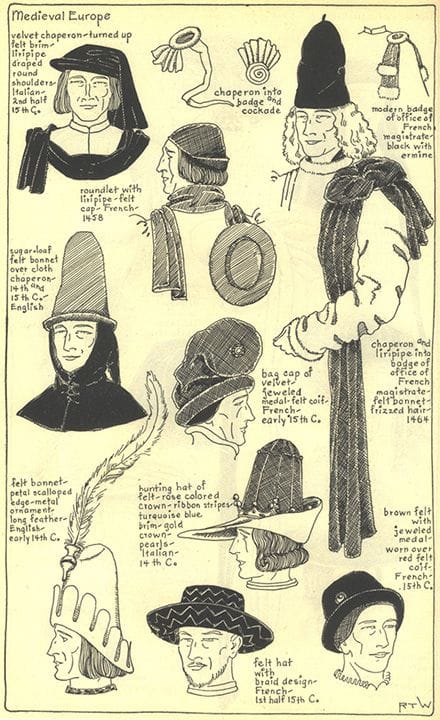

As Europe came under the sway of Christianity, pastoral influences increasingly dominated dressing, both for the clergy and laypeople, with a particular emphasis on head covering. Commoners wore Phrygian caps or hats in straw. Silhouettes, simple to begin with, became complicated and layered. Developments include the Goget, which was a kind of hood, and the coif, a unisex linen cap. Gradually the hood became more prolonged, and bands were added, using velvet, fur, felt, and leather.

With the Renaissance, hats became shorter, some almost beret-like. Men and women conveyed status with elaborate plumes and feathers, most often fashioned from exotic birds and trimmed with rare furs.

Increasingly, commoners took to headgear, though naturally, this was not extravagant in their case, but more like simple berets.

With the rise of democracy and its ideals and revolutions in France and America, headgear became far more straightforward and sober. The Industrial Revolution made well-priced apparel accessible to a far larger cross-section, and class differences in clothing became less pronounced over time. The top hat, mainly in silk, and the bowler, were worn commonly, as was the Stetson in the USA. With the rise in leisure activities, Panama and the boater became hugely popular, associated with leisure and travel.

Headgear In the East

The turban is now strongly associated with the Sikh community, but there was a time Hindus, Muslims, and Christians wore it. And it was a strong fashion statement for the bohemian, which it still is. The earliest evidence comes from Mesopotamia, where a sculpture from 2500 BCE wears a turban-like headgear. Still, turban-wearing was prevalent all across Africa and the Middle East, serving as protection against the elements. They often served as markers of religion, with Christians in blue, Muslims in white, and so on.

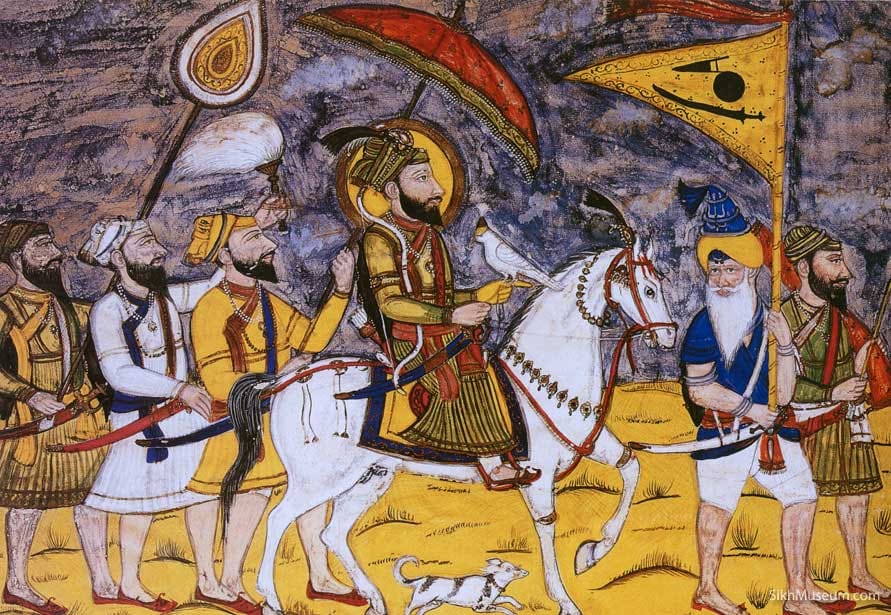

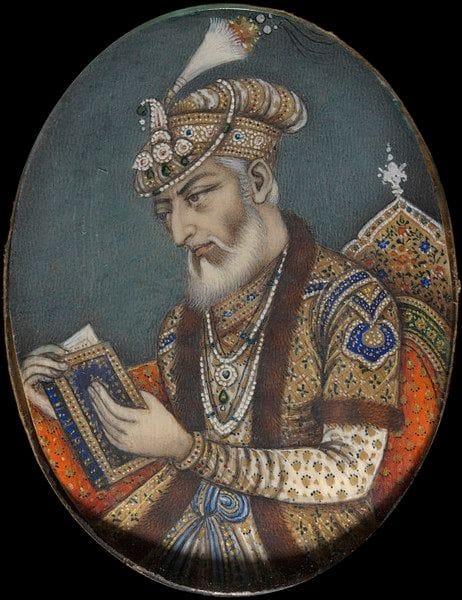

Turbans served as a mark of status in India and were sported by the elite, often embellished with plumes and jewelry, especially from the Mughal era. This era saw the emergence of turbans influenced by the Persian style, larger and broader than their predecessors.

As the Sikh community grew in western India and faced persecution by Aurangzeb, they adopted the turban as a marker of belonging to the community and fraternity and equality. With the coming of the British, they increasingly recruited Sikhs into the army and made the turban compulsory for all soldiers, making all religions and caste equal visually.

In current times, of course, turbans are worn by Sikhs, and in weddings, by both groom and his entourage. Common textiles used are Rubia, muslin, voile, and of course, silk for ceremonial occasions.

Headgear in Contemporary Times

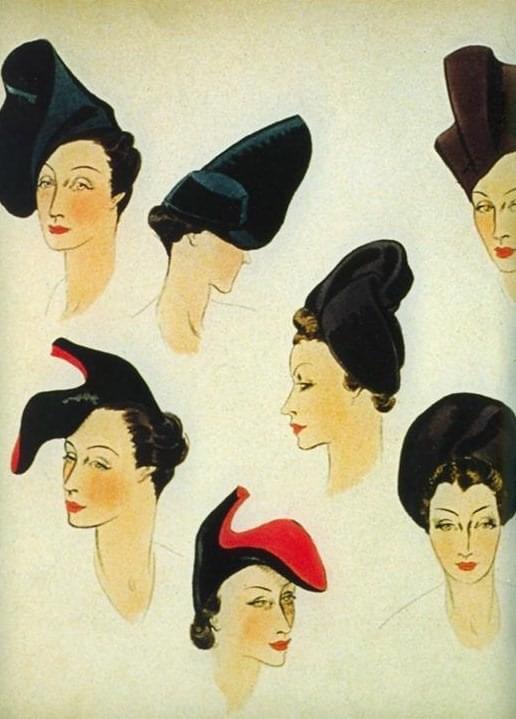

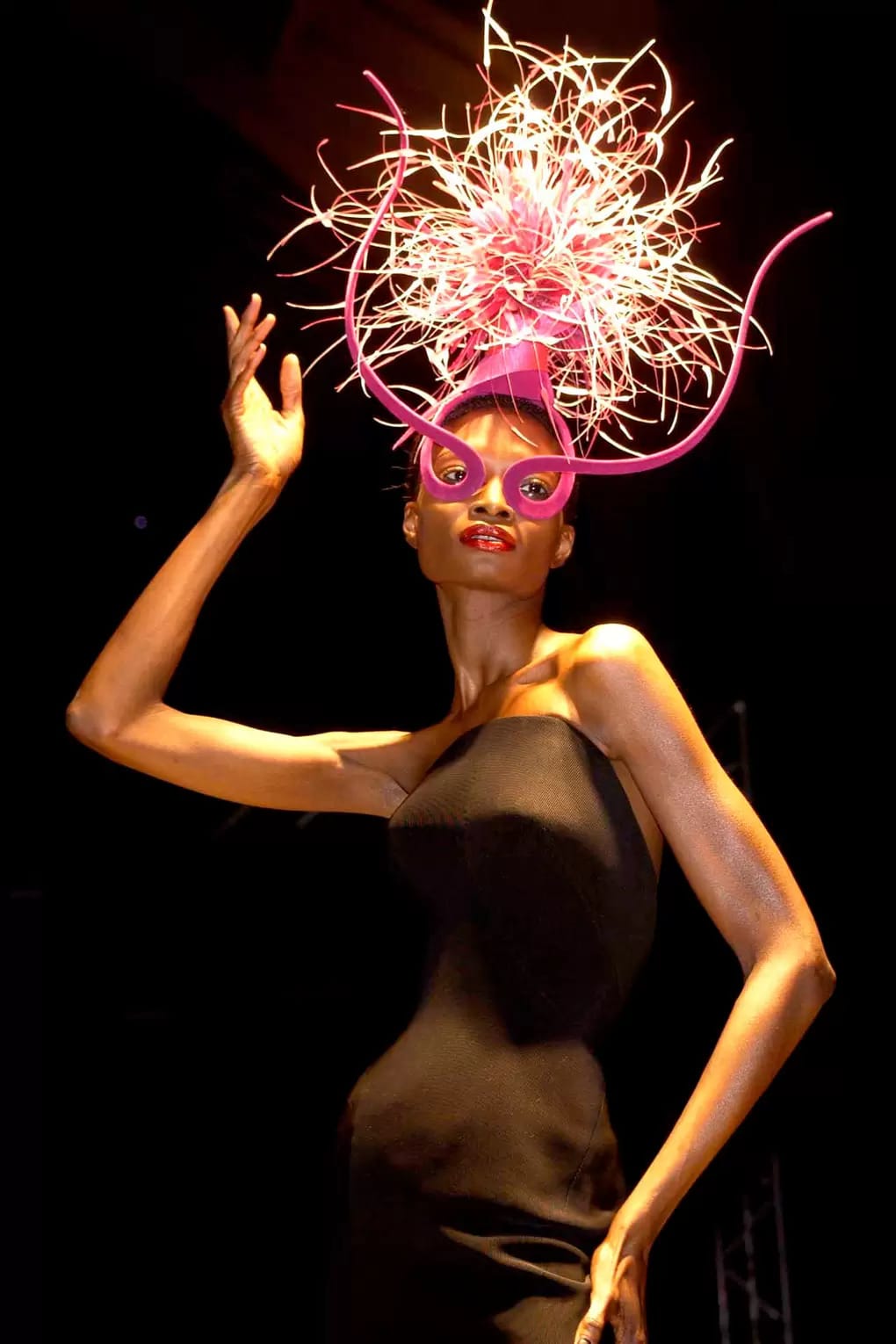

While headgear appears regularly at fashion weeks worldwide, it is no longer commonly seen in daily life, other than in pop culture and for the outdoors. Many young men are firmly attached to their beanies or the hoods of their sweatshirts. And, of course, there’s a whole industry around headgear for outdoor pursuits. Having said that, the 20th century has seen some fantastic headgear design. I’m continually amazed at the surrealist headgear of Elsa Schiaparelli, which are works of art in themselves and are displayed in museums, as are the iconic designs of Philip Treacy, the most famous milliner of our times. Worn by royalty, both literal and celebrity, and of course by his muse Isabella Blow, his hats always turn heads.

AUTHOR BIO

Mira Gupta is a well-known curator and designer in craft-based luxury. She has had working stints with Fabindia, Good Earth, and Ogaan to promote the cause of craft. She is deeply interested in art, travel, architecture, and culture.

Read more articles by the Author HERE

No Comments