25 Sep Handwoven Diaphanous Muslin, The Story of the World’s Finest Fabric

Muslin- The word ‘Muslin’ is believed to derive from Marco Polo’s description of the cotton trade in Mosul, Iraq. Another view is that of fashion historian Susan Greene, who wrote that the name arose in the 18th century from mousse, the French word for “foam.” The word is most likely derived from the port of Machilipatnam, called Masulipatnam earlier, from where muslin was exported to South Asia, the Roman Empire, Ethiopia, and Egypt, where it was famously used to wrap mummies. It was often traded for ivory and rhinoceros horn by Greek and Arab merchants.

THE STORY OF INDIAN CALICO THAT CHANGED THE WORLD

HOW DO YOU SOURCE SUSTAINABLE COTTON

THE STORY OF INDIAN COTTON

THE STORY OF PRINTED AND PAINTED COTTON FROM INDIA

The cloth was so fine that it could pass through a ring, and so diaphanous that a woman’s body could be discerned under seven layers. Amir Khusrau, the Sufi poet in his text Nihayatul-Kamaal, described wearing it as smearing the body with pure water. Aurangzeb scolded his daughter Zebunissa for wearing a transparent dress in court, and she reassured him that she was wearing seven layers of muslin.

Handwoven Diaphanous Muslin from the Indian Subcontinent

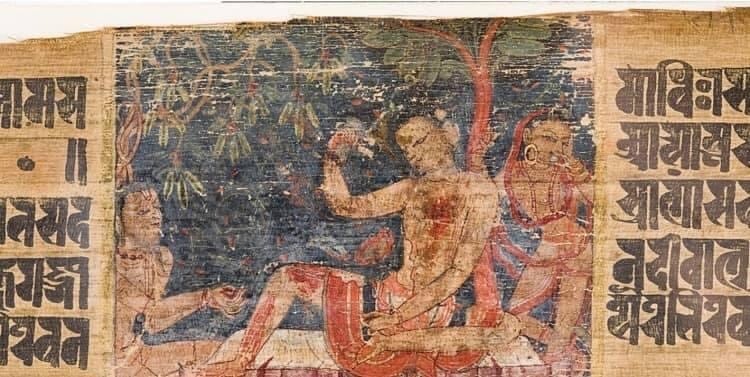

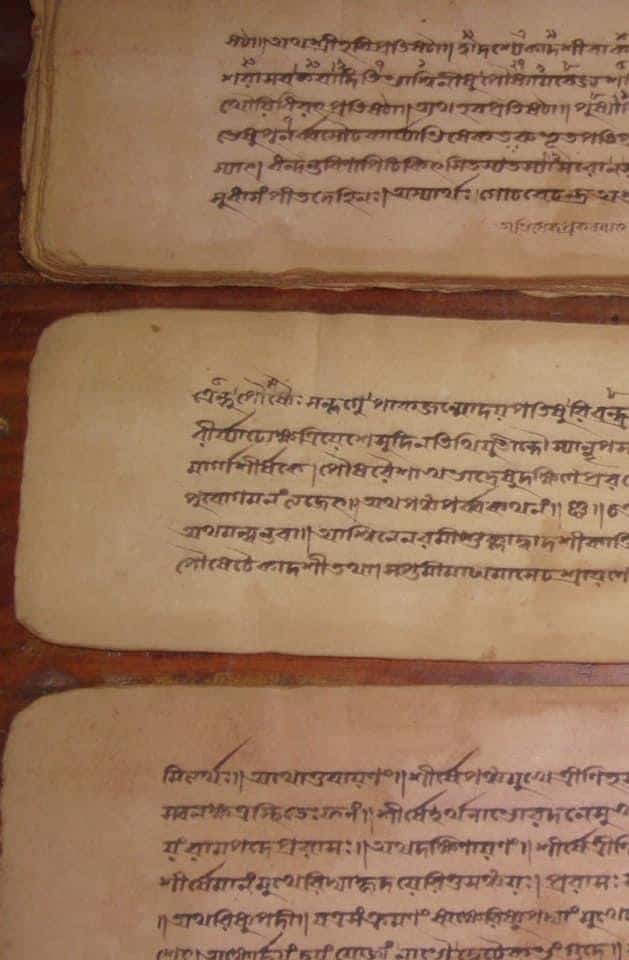

Muslin was produced in Orissa and Bengal, with the finest quality coming from Dhaka. It finds a mention in Megasthenes’ writings and is supposed to be the fabric worn by the terracotta figurines of the 2nd century BCE found at Chandraketugarh. The Charyapadas of the 10th century, which are written on palm leaves, carry a complete description of the process of weaving muslin in the oldest form of Bengali.

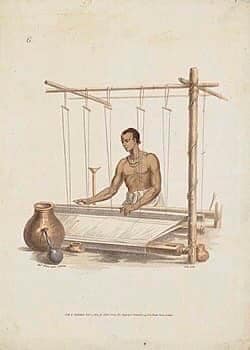

Muslin was woven on the pit loom, which has remained unchanged throughout history. Made of bamboo and rope, it had a pit below from where the weaver operated the treadles. What a marvelous paradox that something as basic as a pit loom should produce a fabric that captured the imagination of so many.

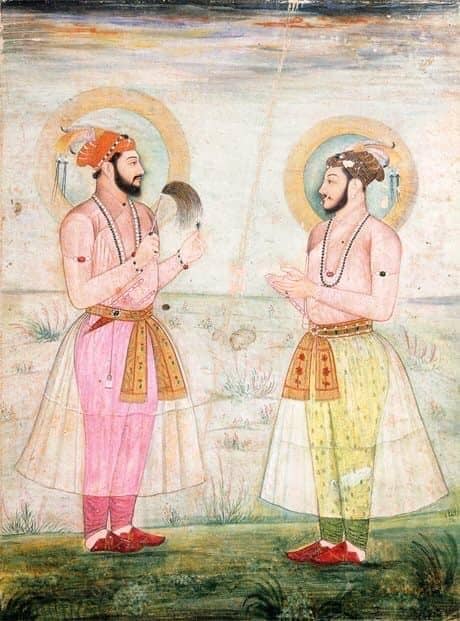

Muslin During the Mughal Rule

Muslin reached its peak under the Mughals when it was given fanciful names such as abi-rawan (flowing water), baft-hawa (woven air), and shabnam (evening dew), and became the most lucrative of all textiles exported from India, with the finest muslin fetching a high price. With their beautiful aesthetics, the Mughals wore it as a Jama, often embroidered with the finest chikankari, with which it is associated to this day.

MUGHAL & DUTCH: A CULTURAL BRIDGING OF 2 GREAT ARTISTIC TRADITIONS

Muslin post the arrival of East India Company

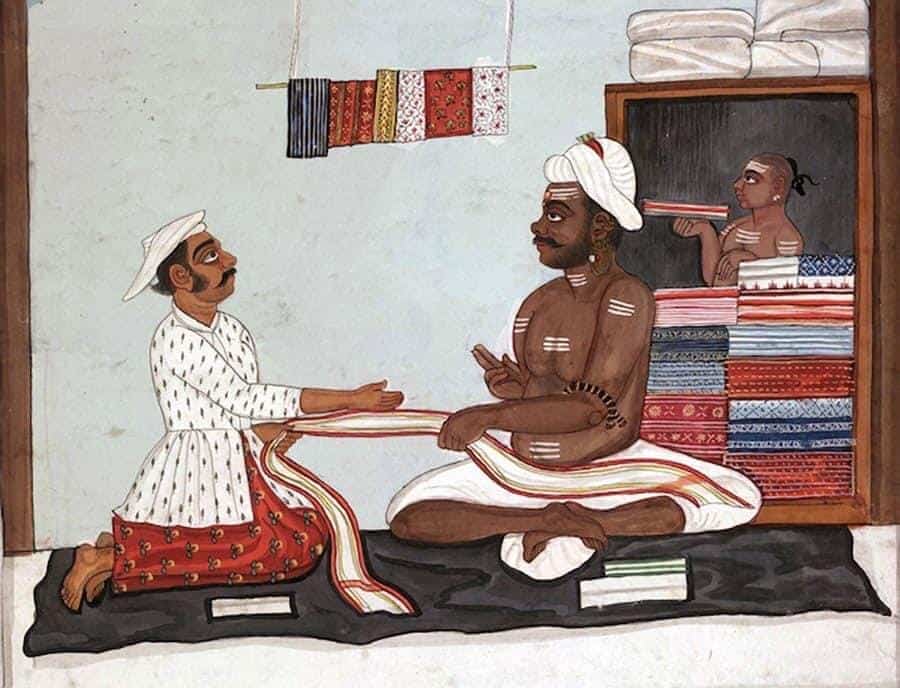

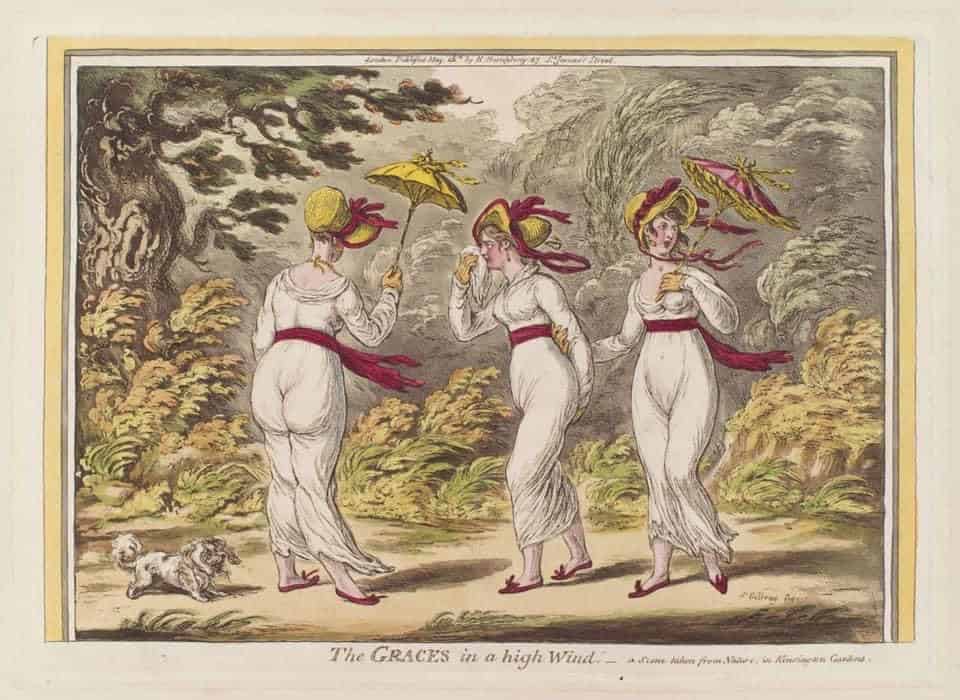

When the European East India Companies became active in India, muslin was exported in huge quantities to Europe from Bengal and Chandernagore. Like chintz, European women enthusiastically adopted muslin, who had so far worn wool and silk, which were expensive and not washable. Tastemakers like Queen Marie Antoinette and Queen Josephine of France helped set the trend for light, airy muslin dresses, which peaked in England’s Regency period.

The industry in muslin was killed by the British after the Battle of Plassey in 1757 when they started ruling Bengal, with their exploitation of artisans and prohibitive tariffs. There are stories of weavers’ thumbs being cut off by the British to prevent them from working. Occasionally the weavers cut their thumbs off to escape the slavery of the British.

As muslin production slowed, the ‘phuti karpas,’ the plant that yielded the finest cotton, gradually became extinct in Bangladesh. Interestingly, a catfish’s upper jaw was used for combing karpas to clean it before ginning and spinning.

Eventually, mills set up in Lancashire produced so-called muslin on mechanized looms exported to India in such massive quantities that it killed muslin and other famous Indian exports like chintz. Jamdani, called ‘figured muslin,’ was the only version to survive.

Difference between Muslin & Cotton

I am often asked what the difference between muslin and cotton is. Muslin is a cotton fabric but much finer than the average cotton, with a looser weave and a higher thread count. Traditionally, muslin came in several grades, with the highest grade malmal for royal use, and then jhuna for dancers and seerbund for turbans.

Lately, there have been laudable attempts in Burdwan in W Bengal and Dhaka to revive fine muslin, though ‘phuti karpas’ is extinct. Some revivalists are producing 500 count muslin, though in small quantities. Such an enterprise needs support from all of us so that this remarkable textile legacy can continue.

No Comments