04 Sep Animal Pigments – the History of extraction of beautiful Natural Pigments

THE HISTORY OF EXTRACTION OF NATURAL DYES-ANIMAL PIGMENTS

Can you imagine a world where all our apparel, our interiors, the objects we use in our daily lives were a uniform white or grey? We take color so much for granted that we cannot imagine that this was the case at the dawn of humanity. As civilizations started flourishing in Asia and Egypt around 2500 BC, the human need for adornment and self-actualization asserted itself in the first use of color. These early colors were derived from minerals, plants, and animal sources, the last involving occasional cruelty. Let us look at the history of color extracted from animal sources in this article.

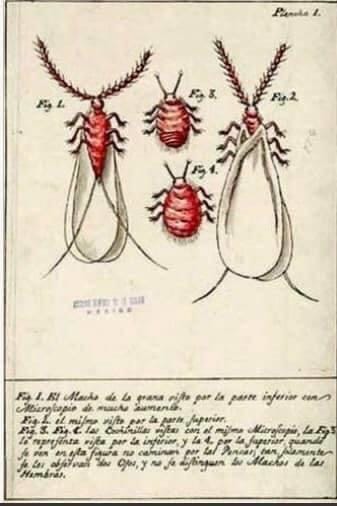

ANIMAL PIGMENTS: COCHINEAL

The cochineal story is a gripping one, not just because the dye is extracted from the cochineal insect, a tiny parasitical creature found on the prickly pear cacti. Pinching it produces a blood-red color, the color that humans have responded to viscerally for centuries. The search for red had proved elusive before cochineal, with henna, brazilwood, lichens, and madder failing to provide the right unfading hue.

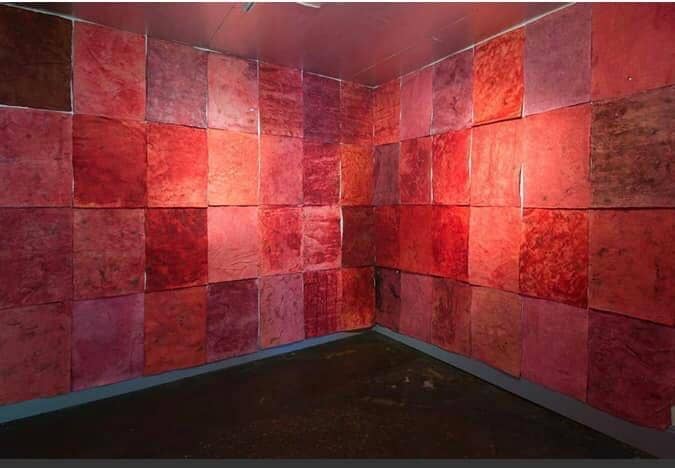

When the Mesoamericans discovered the secret of the cochineal insect thousands of years ago, it was transformed into the most valuable insect of history. Large tracts of highlands in Mexico were used for cochineal cultivation, gradually perfecting the red obtained. The color was derived from female insects, which contained carminic acid, 70000 dried insects required to yield one pound of dye. The array of reds extracted was used widely in Mexico and Central America for textiles, cosmetics, interiors, and art.

The insects were collected by hand from the cacti, dried, and then processed by immersion in hot water or exposure to sunlight, steam, or an oven’s heat. Each method produced a different color.

Eventually, the Spanish conquistadors in Mexico made it their most valuable export to Europe, shipping massive quantities of the dried insect, a cargo just as valuable as silver, the other export from the New World.

Europeans were delighted both with the source as well the hue and adopted it with enthusiasm. The dye was used in paintings and to dye fabrics, most notably the uniforms of British officers.

Eventually, the dye disappeared, with the invention of synthetic reds in the 19th century. But the cochineal market is booming again in current times, fuelled by the current demand for sustainable and natural.

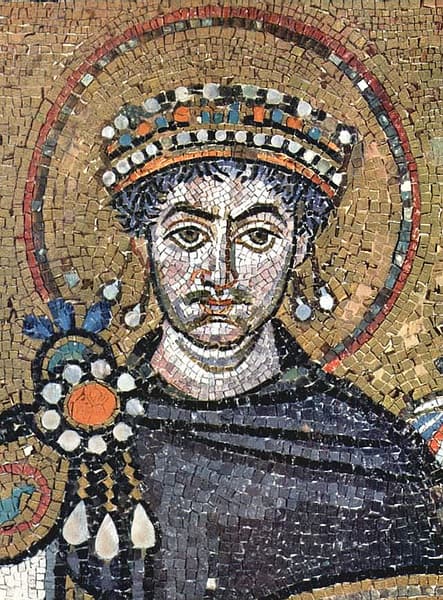

ANIMAL PIGMENTS: TYRIAN PURPLE

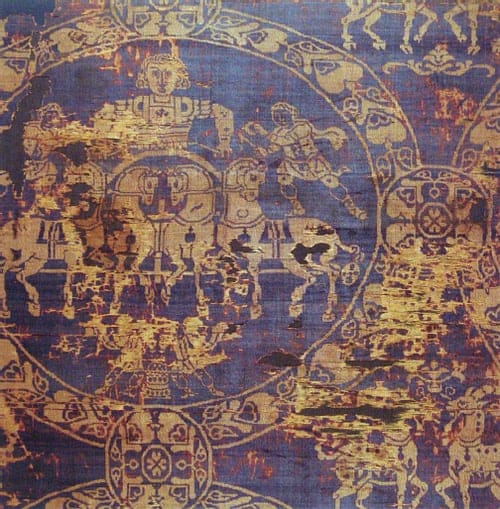

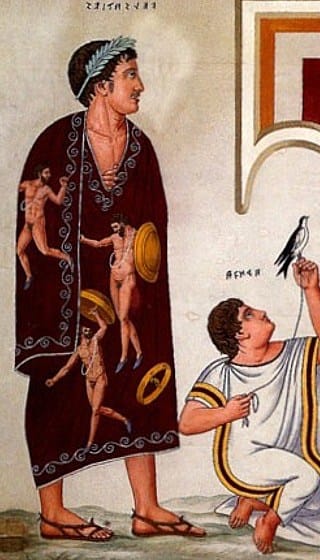

Tyrian purple represents the greatest paradox in the history of color. The color that has traditionally been associated with royalty is extracted from the rectum of the murex shellfish. From the 16th century BC, and most likely in Phoenicia(purple land), thousands of murex sea snails were gathered, dried, and boiled to yield a purple lustrous non-fading hue. Because 10000 snails were required for just 1 gm of color, it was fabulously expensive and affordable only by the elite—the reason why it’s been associated with royalty ever since.

Phoenician myth credits the discovery of purple to a dog which belonged to Tyros, the mistress of Melqart, the god. Tyros spotted a dog chewing on a snail while out for a beach walk, which turned his mouth purple.

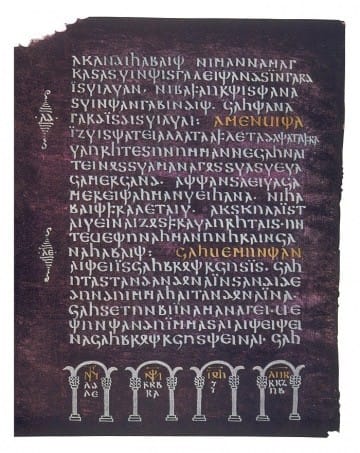

Tyrian purple was used primarily to dye textiles, where it gave far better results than the lichens and whortleberry that had been used so far. It was used occasionally for texts and manuscripts. The porphyry marble, which was very popular in Ancient Rome, became so because of its purple color, now associated with pomp and luxury because of the dye.

A few dedicated hobbyists continue to extract the dye in the old fashioned way, but it’s used now in a tiny artisanal context.

ANIMAL PIGMENTS: INDIAN YELLOW

The yellow pigment known as Indian Yellow has a history as layered and mysterious as its country of origin. The color of the moon in Van Gogh’s Starry Night is derived from cow urine and not just any cows. Cows force-fed on mango leaves.

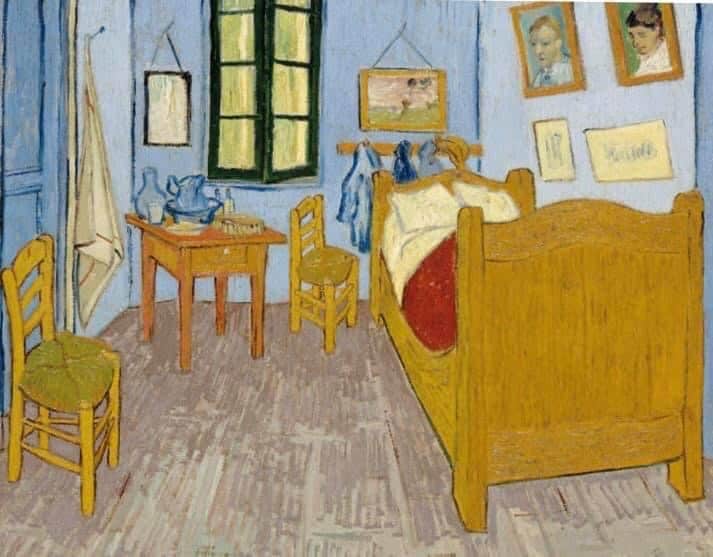

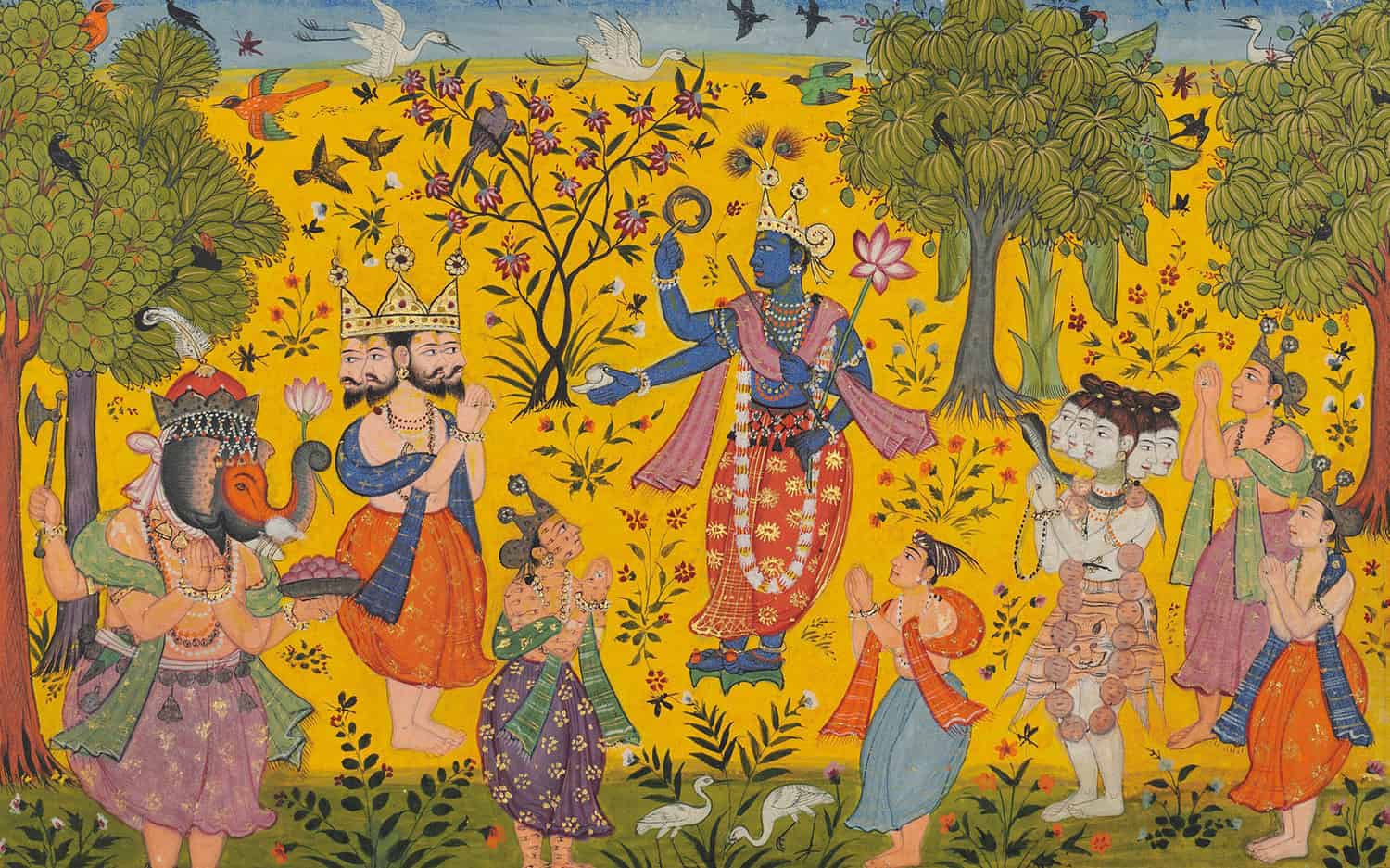

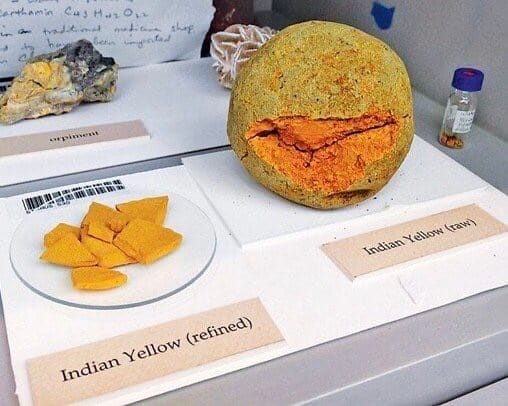

In the 16th century and later, Indian yellow was used liberally in that period’s miniature art. The color was later exported to Europe as compact balls, brown outside, and yellow inside, with a terrible stench. Van Gogh, Vermeer, and Turner, amongst others, all used it for their rich yellow hues.

New research clearly establishes that the Peori, as it was called in India, was derived from cows fed on mango leaves. Their urine was collected, cooled, and then heated to precipitate the yellow pigment. The sediment was made into balls that were dried in sunlight.

Unfortunately, these cows suffered immensely because of their restricted diet and developed jaundice or kidney stones. Mercifully, the process was banned in the early 20th century because of the animal cruelty involved.

The late 19th century saw the invention of synthetic dyes, which were cheaper and more lasting than their organic avatars, putting a virtual end to animal dyes. But with the innovation also went the romance of the story of color.

No Comments