07 Sep Afghan War Rugs and Khamak Embroidery

Afghan War Rugs: I made my first-ever Afghan friends in 2017 in India during the Global Entrepreneurship Summit co-hosted by India and the US Department of State. I remember my excitement to meet so many fellow women founders solving problems in their communities worldwide. However, I want to emphasize the challenges amidst which our Afgan women friends were building their companies were beyond our imagination. They were building their companies amidst the looming threat and past scars of ideological and military war.

From Carpet to Combat The Art of Afghan War Rugs

One of my Afghan friends was a charming young founder of a fashion label. She made a collection of men and women’s clothing using Afghan heritage embroideries. She could not get any formal training in fashion since when she was growing up, there was no fashion school in Afghanistan. Therefore, she learned everything organically, watching and assisting the women in her family. I find her grit very remarkable and inspiring.

Nevertheless, her garment collections were my first introduction to the textile crafts of Afghanistan. Moreover, my recent sighting of Afghan textile craft was at a thought-provoking exhibition ‘From Carpet to Combat The Art of Afghan War Rugs,’ at the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe.

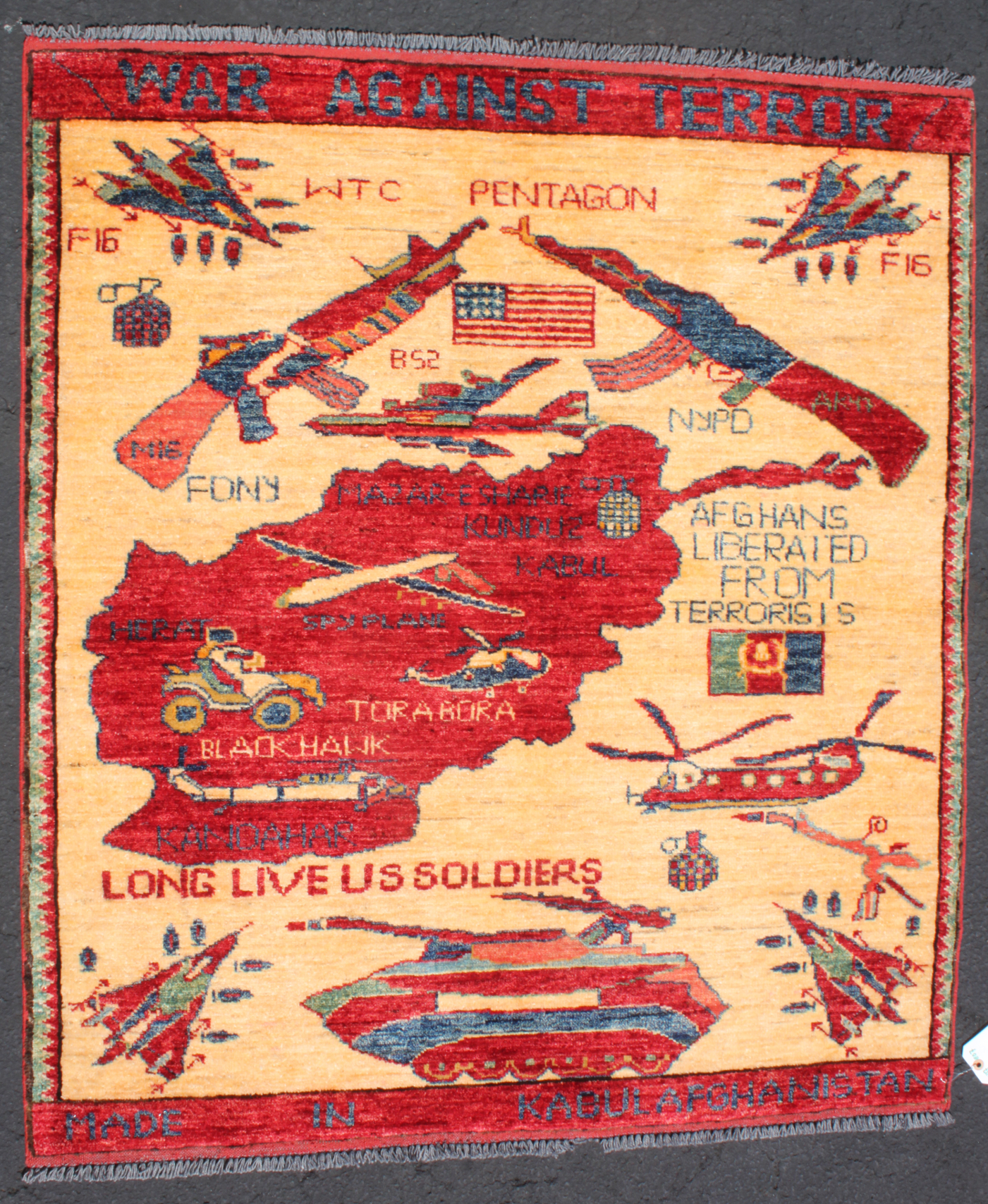

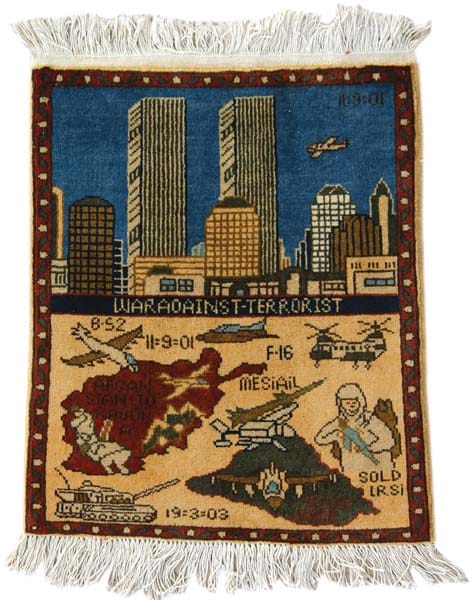

In the words of the curator of The exhibition ‘From Carpet to Combat The Art of Afghan War Rugs,’ “Afghan war rugs gained international attention following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 when millions of refugees began fleeing to neighboring Pakistan and Iran. The rug producers, provoked by decades of traders and invaders in their country, adapted traditional motifs and compositions, transitioning them into depictions of world maps, tourist sites, weapons, and military figures.”

The irony of Afghan Rugs

The war rugs became a means of livelihood for the displaced rug makers and artisans in the foreign land. What I find really thought-provoking are the sentiments of the makers, who have lost their own homes but have the skill to adorn other people’s houses albeit with designs inspired from the war iconographies. And the biggest irony in this is that the primary buyers of these rugs were people who waged and perpetuated these wars. As one story goes, by transforming a paisley motif into a tank, a cypress tree into a missile, or a pomegranate into a grenade, the women weaver wanted to communicate that your brutal killing machines are under our feet.

Afghan Khamak Embroidery

On that note, another Afghan textile technique imbued with the story of the grit of many repressed women, who, in the process of integrating their broken selves from the years of wars, have resurrected languishing, rather challenging embroidery technique called Khamak embroidery. As per an excellent revival initiative by a brave Afghan woman ( name and organization discrete for safety purposes), “Khamak, an intricate form of embroidery, is worked in silk thread and is a trademark of Kandahar. Inspired by complex Islamic geometric patterns, Khamak is unique to Kandahar and is considered by art experts to be one of the world’s finest embroidery techniques. It is traditionally used to decorate the striking, floor-length shawls worn by Southern Afghan men, as well as table linen, women’s head-coverings, and girls’ wedding trousseau. In Southern Afghanistan, women rely on their men to be the exhibitors of their fine art, and men have naturally learned to “show-off” publicly with the best-embroidered work on their attire.”

There are many more textile stories from the land of Hindu Kush mountains that I will keep sharing in future articles.

The purpose of highlighting these stories is to bring home a message that while our industry vehemently raises its voice against the social injustices done to the fashion artisans, it forgets to acknowledge the individual traumas and cultural stories of each artisan. If we recognize that, we will find ourselves with a changed perspective related to their contribution to the industry. We will start seeing profound narratives in their collective body of work. And hopefully, a considerable shift in how they should be valued in our design and manufacturing systems will occur. We need to slow down and appreciate cultures around us and respect those who preserve them.

Read More

THREADS OF LIFE BY CLARE HUNTER – A BOOK REVIEW

AINU, A JAPANESE COMMUNITY THAT REVERES TEXTILES

MACRAME, A KNOTTING TECHNIQUE WITH A LONG HISTORY AND GREAT APPEAL

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Nidhi Garg Allen is an alumnus of Parsons School of Design and Adjunct Professor at the Fashion Institute of Technology. She is a technologist turned artisan entrepreneur and the founder and CEO of Marasim. Marasim based in NYC is committed to preserving artisanal textiles that make use of regional techniques without uprooting craftspeople from their native communities.

Nidhi Garg Allen is an alumnus of Parsons School of Design and Adjunct Professor at the Fashion Institute of Technology. She is a technologist turned artisan entrepreneur and the founder and CEO of Marasim. Marasim based in NYC is committed to preserving artisanal textiles that make use of regional techniques without uprooting craftspeople from their native communities.

No Comments